What are the key components of resilience?

The main components used to measure resilience differ depending on which scale you go by, and which person you ask. Your mom, for example, might say hard work. Social media might say resilience is following your dreams. But what of the scientists and psychologists?

Even in scientific circles, the notion of “resilience” is a fluid concept with multiple meanings. There are several resilience tests floating around, but until recent years there has been no definite consensus on the main dimensions of resilience – or even on what resilience is.

Resilience is a slippery concept, but it can loosely be defined as “advancing despite adversity” (Rossouw & Rossouw, 2016). The key elements of resilience, therefore, are the dimensions of life that help you not just to bounce back, but also to thrive in the face of any challenge.

The Predictive 6 Factor Resilience Assessment Scale, or PR6, is a newer, internally consistent scale based on this definition of resilience. The PR6 was devised through examining existing models of resilience and then combined with neurological models to uncover the main cornerstones that come together to create “resilience”.

The domains as found by the PR6 are Vision, Composure, Tenacity, Reasoning, Collaboration, and Health.

Vision

Vision is the most critical of the domains – the guiding light for all the others. The domain of covers an individual’s sense of purpose, their goals and ambitions. Vision creates clarity through any situation, and Vision is strengthened by having congruence in your goals – meaning that everything across your goals for yourself, for your life and relationships, short and long term, work together and have no conflict.

Composure

Composure is all about emotional regulation. A key component of resilience is being able to control the fight or flight response, downregulating the limbic system and keeping the prefrontal cortex in control. Composure also involves interpretation of events; neutral situations are interpreted as such – or even positively.

Reasoning

The domain of Reasoning covers the creative problem solving needed for thriving in the face of challenge. However, Reasoning is not restricted to reactive action, but also includes the proactive – planning in advance for possible obstacles. Reasoning involves building the skill of resourcefulness, working to build wider nets of tools, techniques and people.

Tenacity

The domain of Tenacity sounds a lot like resilience! Tenacity is about the persistence of a person through every situation. Tenacity includes learning from mistakes without admonishing ourselves – but rather analysing from an objective standpoint. The most tenacious individuals have “realistic optimism” – they are hopeful for success but realistic about challenges.

Collaboration

Collaboration is a domain that runs deep in our evolutionary wiring. Our minds are deeply woven into the social fabric of our communities, and we are intricately designed for intimate connection with others. Collaboration is essential for resilience; the better our perception of our support network, the better we bounce back.

Health

Health covers nutrition, exercise, and sleep. The health domain hasn’t been included in past mainstream resilience tests, but new research by Rossouw & Rossouw (2016; 2017) shows that Health is a “foundational” domain – it supports all the others. For example, it’s hard to align your goals and think creatively about problems if you haven’t slept in a week.

What is a resilience test?

A resilience test, also called a scale, assesses the key dimensions of resilience. Tests are usually administered as a questionnaire.

A resilience test can tell a person roughly how well they engage with hardship. There are several different types of resiliency tests and reports – some more scientifically verified than others.

Can we quantify resilience?

Resilience has been difficult to measure in the past because it’s a fluid concept with multiple meanings. However, we can quantify where people fall on measures of the different dimensions of resilience. This is particularly helpful for comparing different groups of people, and for measuring improvement in resilience over time.

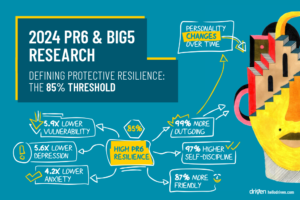

For example, the PR6 provides a resilience report with a score out of 100, with a population average of (something). Knowing where you or your employees or client fall on a definite, numbered scale is a simple way to know who needs assistance where and for how long.

What determines resilience?

Resilience is defined by the ability to advance despite adversity. A person’s resilience can be affected by their childhood, genetics, life experiences, beliefs, and parental modelling – however, resilience can be changed, improved and learned like any other skill.

In 1961, researcher Norman Gamezy began studying what would eventually become a four-decade-long research project: resilience in kids. He was fascinated by what he termed “invincible children”, the kids who – despite multiple stressors and adverse backgrounds – seemed to thrive above and beyond others in their peer group without the same obstacles.

What enabled these rare children to be protected from the difficulties of their childhood?

Gamezy went into schools and asked about the children who were doing well despite difficulty. There was always a pause. Ask about troubled children, and those names come easily – but successful children with problematic backgrounds? They take a moment to identify.

Gamezy separated all the elements of the children’s’ lives into risk factors and protective factors. Which factors contributed to resilience? Which correlated with poor outcomes?

His work was subsequently expanded on by other studies, which discovered that while some of the protective factors had to do with luck environment – for example, a strong connection with a close adult – another factor was at play: mindset.

Or, in technical terms, an “internal locus of control”. These resilient children believed they could impact their world, instead of the other way around. They were victims, but perceived their circumstances as continually presenting challenges that could turn into opportunities.

Of these children from adverse backgrounds, about two thirds would seem to follow the trajectory set out by their childhood, and a third would thrive.

Unfortunately, they found that sometimes even the resilient children had a breaking point. Too many stressors at a point of vulnerability and the locus of control might shift in their perception.

On the other hand, some children who weren’t initially resilient learned how to develop the mindset and went on to achieve success.

Thus, research in recent years – having established that resilience is a skill that can be learned – has focused on exactly how it could be developed.

At the heart, resilience is a way of existing in the world; an understanding that you hold the ability to impact your own life. The PR6 describes this mindset as Vision. However, all the other domains contribute as well:

- Composure allows you to control emotions to focus on your goals and purpose.

- Tenacity helps you bounce back quickly, giving confidence through a particular mindset,

- Reasoning helps you to think creatively and problem solve through challenges.

- Collaboration gives you a support network.

- Health is the foundation of all the others – a healthy body is a healthy mind, and a healthy mind is a resilient mind.

Why measure resilience?

It’s important to measure and track resilience on multiple levels, including both individual and economic.

On an individual level, assessing a person’s level of resilience allows for analysis of their momentum and their comparative resilience against others. This, in turn, is critical for identifying and then rectifying areas of resilience which may need improvement.

On an economic level, the productivity of a nation depends on the productivity of each individual person. The more resilient each person becomes, the more a nation will flourish. Resilience has been empirically demonstrated to improve mental health – thus developing a resilient workforce will greatly improve economic health.

In Australia, the cost of mental health is 4% of the GDP or $4000 per taxpayer per year, a cost of about $60 billion total (The National Mental Health Commission, Australian Government). According to the World Health Organisation, the estimated loss to the global economy from depression and anxiety is $1 trillion.

How can we quantify resilience?

We can quantify resilience by defining the different aspects that make up a resilient person, as verified by empirical data, and contrasting those dimensions against other’s dimensions. Once an average is determined, resilience can be assigned specific measurements which allow for detailed analysis.

There’s currently no specific biological measurement – there’s no brain chemical or neurotransmitter that can be consulted for exact resiliency. However, resilience measurements can accurately describe the relative resilience of the individual to their context.

Resilience measurement frameworks

Resilience measurement frameworks are scales that report resilience according to a particular definition of what resilience is. Resilience measurements vary in scope, in target demographic, and in their conceptual understanding of resilience.

Known resilience frameworks include:

- CD-RISC

- CD-RISC 10

- RSA

- BRS

- SEARS

- READ

- RS

- ARS

- RASP

- DRS

- YRADS

- CYRM

- CHKS

- PR6

According to Windle et al (2011), the resilience measurement scales with the best psychometric properties (prior to the PR6) are the Resilience Scale for Adults (RSA), Brief Resilience Scale (BRS), and the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC).

The BRS measures resilience in its most basic and core form: as “the ability to bounce back from stress”. While the other resilience scales measure personal characteristics, the BRS specifically examines an individual’s ability to recover from adverse events. The BRS has a health Cronbach’s alpha of .8 or over in all the studies testing its psychometric validity.

The CD-RISC also has great psychometric validity to measure resilience and is the most widely used scale (the ten-item version, in particular).

Resilience questionnaire

You can take the PR6 resilience questionnaire here.

Validation of the PR6 scale to measure resilience (in adults)

The PR6 has been shown to have good internal consistency and assess resilience effectively across multiple age groups. Analysis of the items of the PR6 yield a Cronbach’s alpha of α=0.84 (J. G. Rossouw et al., 2019), making the PR6 an effective and valid psychometric tool.

Resilience at Work (and Why It Matters)

Measuring and developing resilience is important in all spheres of life, but there’s a particular sphere in which we should consider carefully when it comes to our ability to thrive in the face of challenge: work.

Imagine the difference between a worker who is resilient, and one who isn’t. One who comes home ready to engage, energetic, and determined; or one who comes home burnt out, dejected, detached. These are extremes, of course, but research shows that the higher the resiliency, the higher your quality of work and life will be.

Resilience at work can help you achieve your ambitions and stay mentally healthy doing it. Resilience is more than just coping: resilience equals thriving.

Reasons Why Organizations Should Pay Attention to Resilience

If you are part of an organisation, consider the return on investment for investing in the resiliency of your workers. Conservative estimates calculate a $4 return for every $1 invested. Employees with higher resilience take less sick days, have fewer days of absenteeism or presenteeism, and return higher quality work.

Consider the attributes you may value on a resume – not the “hard” skills, but the “soft” skills: structuring your day well, being detail-oriented, working collaboratively with people, effective prioritisation, creative problem solving, efficient workload management, etc. In a sense, these skills are more important than the actual hard skill you’re looking for. Not much point in having an accountant who’s great at numbers but gets easily overwhelmed or can’t structure their workload.

Resilient employees are resistant to bad stress – they bounce back quickly and thrive despite the ups and downs of their working life. They are invaluable, but not unique: resilience can be learned and developed in anyone, and in any workplace.

This is crucial at a time in history where the potential of increased automation may mean massive disruptions to jobs across a variety of industries – what economists are calling “the fourth industrial revolution”. As well as this, we’re at a point where culture is shifting inside and outside the workplace, and at a time when mental health issues are on the rise. Given all this instability, it’s important now more than ever to develop people who are healthy, resilient, inoculated from stress and designed to thrive in any circumstance.

Running workplace resilience training could be a great first step!

Building Resilience At Work And Beyond

So how can an individual or organisation build resilience at work?

On the one hand, it requires a fundamental shift in mindset. On the other, this mindset can be enabled by developing skills and thought patterns.

Resilience at work is developed through a range of thought patterns and skills. For example, an argumentative co-worker could easily become a stressor – unless you’re a person with good composure who is unmoved by conflict and sees opportunity in challenges.

A difficult project becomes an opportunity to better yourself and produce something of value under pressure.

A cranky boss becomes an opportunity to develop lifelong skills in conflict resolution and emotional regulation.

By focusing on the key components of resilience, you can thrive in any work environment.

Reviews and critiques of resilience measurement frameworks

Research into resilience by Windle et al postulates there is no “gold standard” of resilience measurement (at least, prior to the PR6).[1]

Further, the resilience assessments before the PR6 have traditionally not included the domain of Health – though Vision, Collaboration, Tenacity, Reasoning, and Composure have all been catalogued before (albeit under different names).

Trends and learning from attempts to measure resilience

A lot of people have failed in their attempts to measure resilience and produce a resilience report. This is due in part to the aforementioned difficulty in defining the definition and domains of resilience.

However, even with an accurate and consistent scale, the human side of resilience measurement has its obstacles: for example, CEOs and people in positions of power or responsibility score much higher than the average – this is partly due to the pressure they feel to maintain a positive facade and to believe the best about themselves.

This tendency can prove to be a true challenge when designing a resilience report. How can the resilience test dip beneath the facade, and test the true resilience of a person? How can the “right” answer not be obvious, while still upholding scientific consistency? Resilience tests must also be scientifically verified to ensure that they are actually measuring resilience and not something else.

Practical guidance on measuring resilience

As an individual measuring your own resilience, there are some key guidelines to keep in mind.

1. Find a good resilience report

There are a lot of resilience tests out there. Make sure to do your research, and don’t trust anything that can tell your level of resilience by asking what colour balloon you prefer or whether you’re a cat or dog person. Favourite ice cream flavours doth not a resilience score make.

2. Be completely honest

There’s no point in taking the test if you’re going to pick the answers you know will get you the highest resilience score. Pick the option that best describes your real behaviour in the last month or two. Not what best describes your entire life – you want to know what trajectory you are on right now, in the present. Make a commitment to give entirely honest answers.

3. Let the results inspire you

Measuring resilience is the first step in taking action. When you realise life is not as good as it could be – or that the people around you could benefit from improving your personal resilience – this is the beginning of learning the skills and behaviours which will benefit you the most. So, when it comes time to read the results, make sure you’re reading them with the intention of taking action.

If you’re part of an organisation, there are a variety of resources to help you run the best workplace resilience training session.

Understanding degrees of resilience

When measuring resilience, there are two questions to ask if you want to understand the degrees of resiliency.

- What is the average?

- What would be healthy?

Your resilience score means nothing if you don’t know where everyone else is at. You need to know the average score for your group to see if there is something about your life that is diverging from the norm in a positive or negative way.

Similarly, just because you know the average, doesn’t necessarily mean that you’re doing well – perhaps something is wrong in your context, in your corporation, or even in your country. Scoring above the average in this case doesn’t equal thriving.

So, to understand what your resilience score means, you will need a rough idea of other people’s resilience, as well as what the ideal might be in your context.

For example, the PR6 provides a chart showing the average either of the population at large (for an individual) or for the organisation you’re a part of.

Reducing adverse livelihood impacts from shocks or stresses

Research by Bonanno shows that events are never traumatic; our perception of events is traumatic. Managing our perceptions is crucial for reducing negative impact on our lives from trauma.

For example, if a close friend passes away, you might find enough meaning in the event that it doesn’t negatively impact you. Or if you lose your job, despite how much you loved it, you may perceive that this event has the potential to be an amazing opportunity, and so become protected from trauma.

In contrast to the idea that most people experience stages of grief, Bonanno’s research identifies resilience as the most common experience of trauma.

Therefore, if we want to reduce the chances of negative impact on our lives, we need to develop resilience. This does not mean you can’t feel sad. Instead, developing resilience in the face of potentially traumatic events is an effort to prevent adverse effects on your life.

Want to learn more about resilience?

To learn more about measuring resilience and resilience measurement, check out the references below for a starting point to the world of resilience psychometrics and research.

Read about the PR6’s development to better understand the components of resilience.

Our pricing for resilience assessment

Driven offers resilience training both for psychologists and coaches, or for businesses. As a certified coach, you can train clients in resilience and access a host of resources. If you are an enterprise, courses are available to train organisations – complete with state of the art metrics to track company wellness, AI-powered coaching, brand integration and portfolio optimisation.

References

Bonanno, G. A. (2005). Resilience in the face of potential trauma. Current directions in psychological science, 14(3), 135-138.

Garmezy, N. (1993). Children in poverty: Resilience despite risk. Psychiatry, 56(1), 127-136.

Olsson, C. A., Bond, L., Burns, J. M., Vella-Brodrick, D. A., & Sawyer, S. M. (2003). Adolescent resilience: A concept analysis. Journal of adolescence, 26(1), 1-11.

Rossouw, J. G., Erieau, C. L., & Beeson, E. T. (2019). Building resilience through a virtual coach called Driven: Longitudinal pilot study and the neuroscience of small, frequent learning tasks. . International journal of neuropsychotherapy, 7(2), 23-41. doi:10.12744/ijnpt.2019.023-041

The National Mental Health Commission, Australian Government

Werner, E. E. (2000). Protective factors and individual resilience. Handbook of early childhood intervention, 2, 115-132.

Windle, G., Bennett, K. M., & Noyes, J. (2011). A methodological review of resilience measurement scales. Health and quality of life outcomes, 9(1), 1-18.